Canada's temporary foreign workers

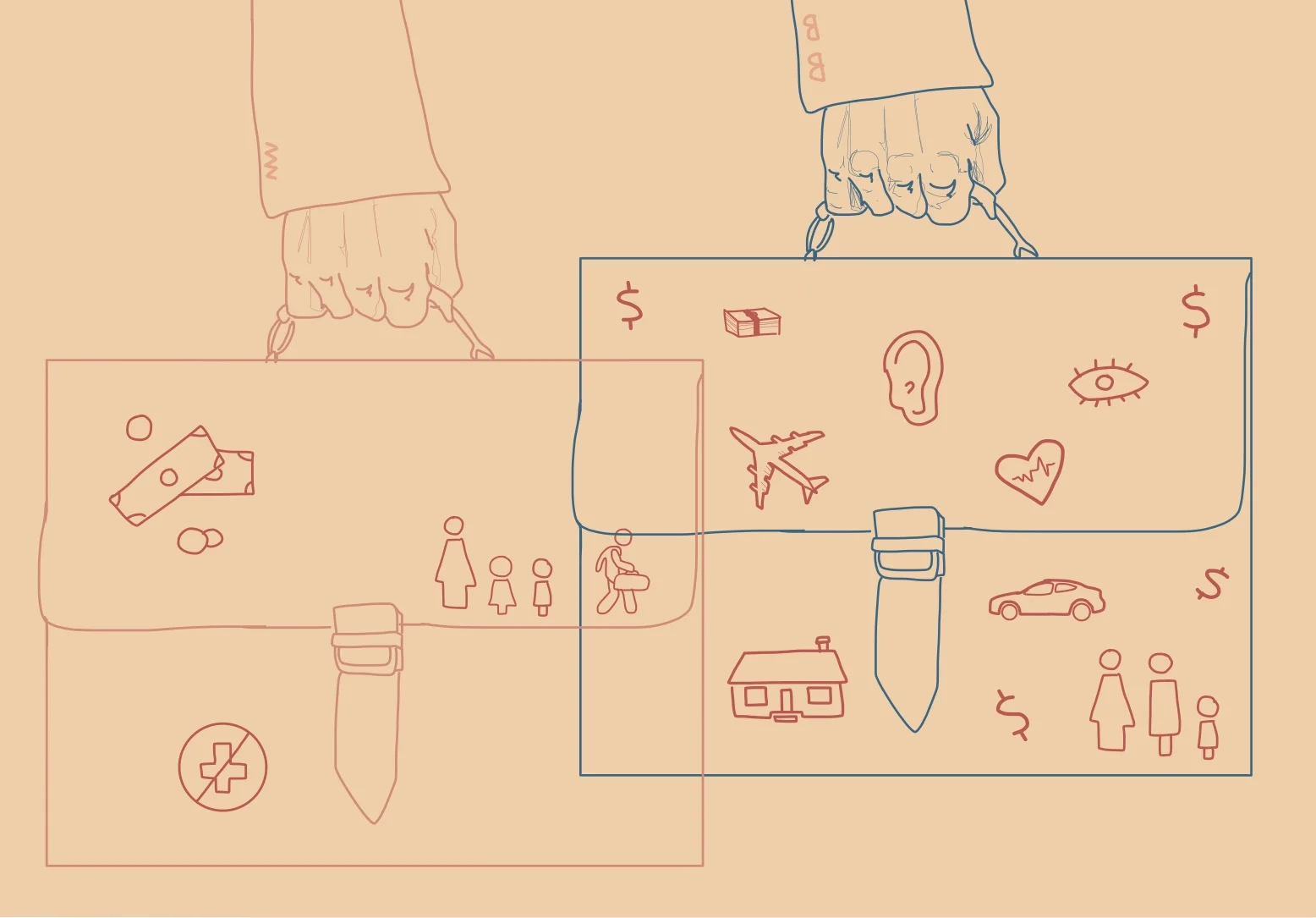

(Kayleigh Valentine / The McGill Policy Association)

In November 2018, Quebec’s unemployment rate was 5.4 per cent and represented one of the lowest in Canada in decades. Yet, in many regions of the province, labour shortages have pushed companies to employ migrant workers who seek better job opportunities and permanent residency. For example, the Beauce region in Quebec has welcomed groups of men and women from Madagascar to compensate for the lack of employees. Companies have also hired asylum seekers to help fill labour shortages. Once migrant workers arrive in Canada, their temporary work permit allows them to be legally employed and work full-time but without the benefits that citizenship or permanent residency entail.

Current policies

The term “migrant workers” refers to foreign workers coming to Canada under a work permit but who do not have a permanent resident status. Under the immigration program, policies put in place for migrant workers fall under the broad umbrella of shared legislative jurisdiction although federal provisions take precedence. Canada’s current program for temporary foreign workers is divided into three sub-programs: the Live-in Caregiver Program, the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program, and the Pilot Project for Occupations Requiring Lower Levels of Formal Training. The most popular program, the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program, allows farmers to bring in labourers for eight months each year. More specifically in Quebec, migrant workers are required to obtain the consent of the Ministère de l’Immigration, de la Diversité et de l’Inclusion (MIDI).

However, the downside of joining this subgroup of immigrants is revealed through several human rights reports and exposés. According to a report by the Commission des droit de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse (The Human and Youths Rights Commission), migrant workers who come to Quebec under temporary work permits are victims of systemic discrimination. The report argues that migrant workers are vulnerable to unfair treatment and live precariously at the mercy of their employers. Furthermore, the Canadian Council for Refugees has stated that the policy shift from permanent migration to promoting temporary migration has put these migrant workers at a higher risk of experiencing discriminatory treatment and limited access to resources. Although migrant workers can file for a complaint with the Commission des normes, de l’équité, de la santé et de la sécurité du travail, labour regulations often overlook migrant workers and place them in a vulnerable position vis-a-vis their employers. For example, immigration officers lack the power to issue new work permits in case of reported abuse, subjecting migrant workers to remain in unsafe work environments. With their visa conditions depending heavily on their living situation and employment, these workers become especially vulnerable. In addition to the isolation induced by working away from their families and facing systemic discrimination, the government deducts taxes and Employment Insurance premiums from their pay although they are not granted the access to resources or any form of benefit associated with citizenship.

In light of such treatment, the commission recommends an independent tribunal to provide these workers with legal assistance in case of unfair repatriation. Although Yves-Thomas Dorval, the head of Quebec’s employers’ council, describes the use of migrant workers as a win-win situation for both companies looking for labour supply and migrants seeking to permanently relocate for better job opportunities, new legislative initiatives are the only way to fully protect at-risk temporary workers.