The exclusion of undocumented migrants in Québec during the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and Solutions

Man in Green T-Shirt, by Jon Tyson, is licensed under Unsplash.

Introduction

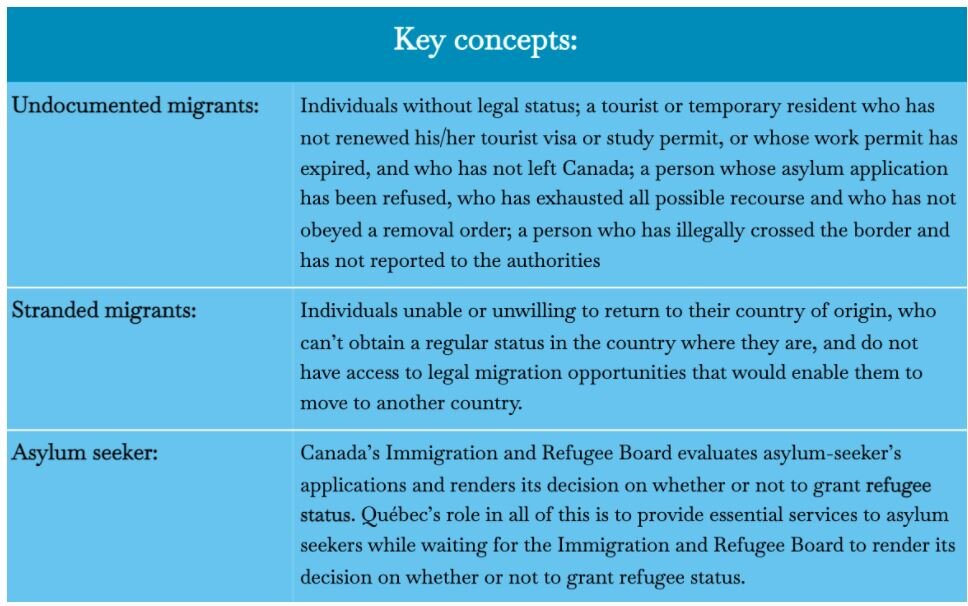

Quebec is a major entry point for migrants and asylum seekers coming to Canada. In 2019, the Canada Border Services Agency processed the highest number of asylum claimants at its air, land, and marine ports of entry in Quebec (over 20,000, compared to about 7,000 in Ontario). Like all other Canadian provinces, Québec’s Ministry of Immigration prides itself on its promotion of immigration and intercultural relations, often contrasting the friendly Canadian image with the events occurring in the USA. Specifically, Quebec’s treatment and handling of migrant cases during the Covid-19 pandemic shows just how much work still needs to be done in order to truly achieve the ‘welcoming approach' and meaningful inclusion and well-being of migrants that it claims to uphold. This first part of the policy brief outlines the issues surrounding and challenges facing undocumented migrants in Québec during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Exporting the pandemic

Stranded migrants and asylum seekers are one of the most vulnerable populations, especially during the pandemic. They have been hit hardest by border controls, as they are often fleeing poor circumstances, such as conflict, natural disaster, or poverty, and rely on entry into another country for their livelihoods. A notorious example of such border controls is the Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA), which states that migrants who land first in the United States cannot claim asylum at a regular port of entry in Canada, which is highly problematic given the anti-immigration policies in the USA. Along with the sweeping COVID-19 lockdown measures, asylum seekers in Canada have been refused at the border or deported to the United States, where risks of family separation, detention of children, and deportation to the country of origin are significantly higher. By complicating the asylum-seeking process and implementing border controls, Canada is sending asylum seekers and other migrants back to countries where health infrastructure is weaker and less capable of dealing with pandemic. The journeys of asylum seekers and stranded migrants should be considered as “essential travel” so that they can safely establish their livelihoods, and so that Canada avoids exporting the pandemic to developing countries.

Exclusion of undocumented migrants from essential rights and services

In addition to complicating and discouraging the entry of asylum seekers and other stranded migrants into Quebec, the Canadian federal government has also made it extremely difficult for undocumented migrants already residing in the province to access basic services. The closing of certain government offices has caused immense delays in handling migrant cases and granting them crucial documentation. For instance, in March 2020, the closure of the tribunal responsible for asylum seekers' applications, the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB), led to all hearings before the Refugee Protection Division (RPD) being canceled. Although hearings in Montreal resumed on August 3 and are proceeding slowly, the closure has caused longer processing times that will add to the delays that were already accumulating before the pandemic. In February and March of 2021, Québec approved only 3 out of 721 applications for the Québec Acceptance Certificate (CAQ).

As the difficulty in receiving and renewing necessary documents like work permits and the CAQ is exacerbated during pandemic due to closures, undocumented migrants find themselves unable to find work or access economic assistance like the CERB. They cannot put their children in daycares either, which also prevents them from working and earning income. Though exceptions were made during the first months of the pandemic for asylum seekers without access to subsidised childcare services, their lack of familiarity with the system and their rights was another obstacle. Some 90% of asylum seekers were refused a place for their child in a daycare, but many more could have been deterred from applying due to such obstacles..

Similarly, many migrants unfamiliar with the system or lacking the RAMQ card have experienced challenges in getting tested for COVID-19. This unfamiliarity with the system can be traced back to the issue of language integration, since access to French language courses is often dependent on one’s possession of a study/work permit and Certificate of Acceptance from Québec—and the process of obtaining these documents is now delayed by up to 6 months. Not only do these challenges place an immediate material burden on undocumented migrants, it is potentially associated with adverse mental health effects. Living as an undocumented migrant is already an extremely stressful process, with the fear of being confronted by the police and dealing with the Canadian Border Services Agency. Now, they must also worry about safety measures and financial security during a pandemic, in a country that is not their own.

There are few statistics collected on just how many people are living and working in Canada undocumented, but it is estimated by some NGOs to be at least half a million across the country, and 50,000 in Montreal alone. Accordingly, this issue should be catching the attention of both the federal and provincial governments.

New federal program lacks details and progress

In response to the immense participation of migrants on the frontlines of the pandemic, the federal government introduced a new program in August to fast-track the permanent residency applications of some asylum seekers working in specific jobs in the health-care sector. The details and progress of the program remain questionable. In terms of progress, vague statements by spokespersons for the Ministry of Immigration announced in August 2020 only that "the application process…will open in the coming months". It could be months or years before those applications are actually processed. There have also been questions regarding the inclusion criteria, such as what would happen if workers' claims were rejected or if a person did not hit the 120 required hours of work because he or she fell ill with COVID-19. Other essential workers who do not work directly with patients are also excluded, such as security guards, cleaning and maintenance staff, farm labourers, and factory workers. These workers, despite the risks in taking public transportation and being in contact with other workers, continued to work during the pandemic. The so-called ‘Guardian Angels’ gathered a large amount of public support, after it was revealed that refugee claimants were among those working in Quebec's long-term care facilities, which were very hard-hit by COVID-19. A key slogan of protests that advocated for granting status for all asylum seekers working during the pandemic was “we are all essential”.

Government action does not align with public opinion

Premier of Quebec Francois Legault started to refer to the asylum seekers working in care homes as ‘Guardian Angels’ as they were critically short-staffed, but in 2017 said on the subject that the province could not accommodate “all the world’s misery”. It became clear how integral the newcomers were in providing support to a strained labour market, which coincided with a shift in public sentiment and the name "Guardian Angels" being coined. Along the same lines, a 2020 study by the Environics Institute for Survey Research at the University of Ottawa recently found that “by a five-to-one margin, the public believes that immigration makes Canada a better country, not a worse one”, and that most Canadians reject anti-refugee and anti-immigration sentiments. It then becomes questionable that the federal and provincial governments are still maintaining so many obstacles for asylum seekers and undocumented migrants, especially in time of global crisis.

Policy Recommendations

In summary, undocumented migrants in Quebec have faced several challenges during the COVID-9 pandemic. These range from systematic hurdles in place at the federal level which deter migrants and asylum seekers from entering Quebec, as well as the exclusion and mistreatment of undocumented migrants residing in the province.

The following recommendations aim to guide both federal and provincial policy in order to increase and improve the integration of migrants, and put an end to their exclusion in Quebec society.

1. Facilitate an easier and more inclusive asylum-seeking process.

The federal government is placing too much emphasis on the assistance of private sponsors. The private refugee sponsorship program allows individuals and groups to help resettle refugees to Canada, and so it is them, not the government, who are responsible for a year’s worth of financial and moral support for the sponsored party. This unsustainable structure needs to assign a greater portion of the responsibility to the federal government in order to ensure more migrants and asylum seekers are welcomed and supported after the initial first year. Furthermore, abolishing the STCA is also a crucial aspect of easing the asylum-seeking process. Recently, the Federal Court of Appeal approved a request from the federal government to temporarily suspend a lower court’s decision that would have ended the Safe Third Country Agreement at the end of January. Canada cannot maintain an unconstitutional status quo that endangers asylum seekers and deprives them of their human rights to liberty and security.

2. Adjust documentation and permit requirements for asylum seekers accessing critical health and employment services.

Many groups and individuals have already spoken out about the injustice inherent to the exclusion of undocumented migrants from assistance and services. A good starting point would be for the government of Quebec to eliminate or reduce the documentation required for French language assistance, as language is one of the main factors leading to successful integration and positive outcomes in areas such as employment and income. Although the French language is a key element of québécois culture, there needs to be a similar importance given to inclusivity. Another viable solution is the expansion of income supports like the Canada Emergency Response Benefit to include undocumented residents and asylum seekers. Already thousands of migrant and undocumented workers have lost their jobs, and as they have limited access to social security programs, they are not able to pay their rent, buy food and feed their families, and are simultaneously at high risk of being evicted and becoming homeless. Income supports could make a huge difference in terms of economic distress, especially in the context of employers being reluctant or unwilling to hire such individuals.

3. Speed up the process of the new Special Program for Asylum Seekers During COVID-19 and ensure adequate inclusion.

While the hard and dangerous work of frontline working asylum seekers is indeed being recognised, the new program should ensure that its selection criteria takes into account non-health sector employees. The Migrant Rights Network has called for a single-tier immigration system under which all migrants, refugees, students, workers and undocumented people in the country are regularized and given full immigration status in light of the pandemic. They note that in addition to the ‘Guardian Angels’, other locations such as farmhouses, where migrants are known to have taken up jobs, were some of the hardest hit by COVID outbreaks. Many migrants employed as domestic workers remain trapped in the homes of their employers, facing greater surveillance, abuse and violence. The new Special Program needs to start accepting and processing applications immediately, and ensure full immigration status for all who need equal rights and protections from a global justice perspective. The Ministries of Labour and Immigration should also recognise the need to implement collaborative measures like labour protections and wage increases for vulnerable migrant communities, in order to address these injustices at their roots.

4. Adopt and promote an overall positive attitude towards welcoming asylum seekers which rejects any notions of exclusion, discrimination, etc.

History is an undeniable part of this story. Canada, having a history of colonisation and systemic racism, needs to address how this fundamentally impacts the immigration policies in place today. To date, there are very little reports and publications on the topic, potentially because of lingering denialism that such issues do not exist in our country - again casting ourselves under a halo while pointing our fingers at the United States. With the pandemic, there is no denying that Canada has seen its fair share of anti-Asian racism and instances of discrimination. Furthermore, the pandemic has also allowed for the exploitation of many migrant groups in work settings. A report by the Migrant Rights Network puts it very clearly how "the racism underpinning this denial of freedom is clear: even as employers [go] in and out, workers — primarily South-East Asian, as well as Caribbean, African and South Asian women — [are] treated as vectors of disease". Both the federal and provincial government need to strictly drive home the message that migrants are welcome and are absolutely not to be met with exclusion, discrimination, or any other form of mistreatment. One way of doing this is related to the previous policy recommendation #3: providing full immigration status would help in many situations, as a lack of permanent residency makes it harder for undocumented migrants to assert their rights. Acknowledging and addressing the systemic racism within the federal and provincial immigration systems is another important part of this recommendation; taking down conscious and unconscious biases that lead to certain discriminatory decision making, and holding stakeholder consultations - undocumented migrants and asylum seekers themselves should without a doubt be part of any such process, including the New Program for Asylum Seekers During COVID-19.

Conclusion

This policy brief has highlighted the issues surrounding and challenges facing undocumented migrants in Québec during the COVID-19 pandemic. To summarize, the Canadian federal government should facilitate an easier entry of asylum seekers and other stranded migrants into Quebec, to stop the effect of exporting the pandemic to countries with poorer infrastructure. The government of Quebec should reevaluate and adapt documentation requirements for essential services and rights, such as access to employment, childcare services, and healthcare. The new Special Program for Asylum Seekers During COVID-19 should address the controversies surrounding its details and criteria, and speed up progress. Finally, government action (or lack thereof) needs to align more with Canadian public opinion, which is much more accepting and pluralistic, possibly by addressing systemic racism in immigration policies. Potential future areas of inquiry include how we can make such changes stick post-COVID, and how we can ensure that these challenges do not occur again. To begin, there certainly needs to be more coordination between the federal government and the provincial government of Québec. In conclusion, the progress already achieved for migrant rights in Canada is comparably worthy of applause, but there is a lot more that goes on ‘behind closed doors’ which needs to be addressed during this pandemic, or it possibly never will be.